Geo Skills

Skills and advice to speed up your progress!

Why care about Geo-Skills?

We’ve called Geo-Skilles the technical knowledge that is commonly used by scientists working in various branches of geosciences. If you are an aspiring geologist, or if you like staying in tune with various issues in the field of Earth science, we are here to help you learn not only the facts (see Geo-Insider) but also how to do your own research on a scientific level.

What content do we have for you?

Here we have prepared for you 3 types of content: explanations, demonstrations, and practice tasks on different technical subjects.

How to get the most out of this?

We suggest you start by choosing a topic from the explanations section, read the details offered, and then continue (a link will be provided) to the corresponding blog post in the demonstration section. Finally, we invite you to check your knowledge by using the practice tasks.

- Research Papers 101

- What is The Scientific Method?

- Literature Review

-

Step #1: Explanation

-

Step #2: Demonstration

- Step #3: Practice

Research Papers 101

For this article we have invited Dr. John Clague to help us. Dr. Clague has been the Editor-in-Chief of two geoscience journals over the course of his career: Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences (1988-1992) and Natural Hazards (2021-present). In the latter position, he is responsible for evaluating about 500 research papers submitted to the journal each year. This position has provided Dr. Clague with a very good understanding of how to write a proper and effecting research paper.

Hover over the questions below to see Dr. Clague's answers!

What is a research paper?

Answer

A geoscience research paper is a technical report that summarizes scientific findings that emerge from Earth observations, laboratory experiments, or modeling. Research papers should be the end product of the application of the scientific method. An effective research paper is written concisely and clearly and avoids a conversational writing style that always leads to ambiguity and uncertainty. The purpose of a research paper is to test or advance science on the topic that the paper addresses.

What is the standard format of a research paper? Why is it that way?

Answer

Most research papers, with the exception of short notes or comments have the following sequential structure: 1. ‘Tombstone data’: Authors’ names, affiliations, contact information 2. Abstract 3. Introduction 4. Study area (if a field-based project) 5. Methods 6. Results 7. Discussion 8. Conclusion 9. Acknowledgements 10. Funding (if applicable) 11. References Figures and tables are either embedded in the text or grouped at the end of the paper. There is always some discretion in the format of a research paper, but the structure outlined above allows authors to present their research in a manner that a reader can fully understand AND abides by the requirements of the scientific method. A common mistake that authors make is to mix up methods, results, and discussion. These should always be separated: results must be verifiable and not subject to speculation. Discussion is the place for the authors to position their research in the context of national and international published literature on the topic of the paper and to state how the research advances science.

What is the most important part of a research paper to understand?

Answer

This is a difficult question to answer, but I think the results are Number 1. Specifically, what is the significance of the results and are supported by the data and methods used by the authors. See also the ‘Extra advice’ section below.

Where can I find research papers on a topic that interests me?

Answer

GeoRef (GeoRef | GeoScienceWorld) is an excellent online tool for finding geoscience research papers on any topic. Unfortunately, it is typically only available through university servers. A good alternative is the Google search engine. If you know the title of a paper you are trying to find, enter the title into Google, and, voila, the engine will bring it up (or at least the abstract). Also, in my opinion, Wikipedia is a good entry point for locating papers of interest. Finally, all scientific papers have a Digital Object Identifier (doi) designation (doi.org). By entering the doi designation for a paper in Google, information on the paper, and in some cases, the entire paper, will pop-up.

What is a “conflict of interest?” Is it always “bad?”

Answer

Authors have a perceived or real ‘conflict of interest’ if the research results they publish have been financially supported by an agency or body that has a vested interest in the outcome of the research. For example, researchers studying the possible environmental impacts of oil and gas production should not have received financial support from a company that produces oil and gas. That is a clear ‘conflict of interest’. All conflicts of interest are bad.

What extra value can I get from the reference section?

Answer

References are a requirement in research papers. They support assertions that authors make in their papers and allow readers, if they wish, to further explore the topics the papers address. Cited papers and other documents position the authors’ work in the typically large body of relevant published research on the topic of their paper. They also allow students and professionals to further their understanding of the topic.

Extra advice:

Advice

When reading a scientific paper, first read the Abstract, then look for the question the paper is addressing (should be in the Introduction). Next, review the Methods to see if they are appropriate for the study. Are the Results justified based on the data and methods. Finally, read Discussion to better understand how the authors’ research is positioned in the larger body of science on the topic that is being addressed. Have the authors advanced science at all. If not, the paper is likely a ‘case study’ that will be of limited interest to you and other readers

Let's take a look at an example of a research paper:

Content written by an Earth Science Matters volunteer.

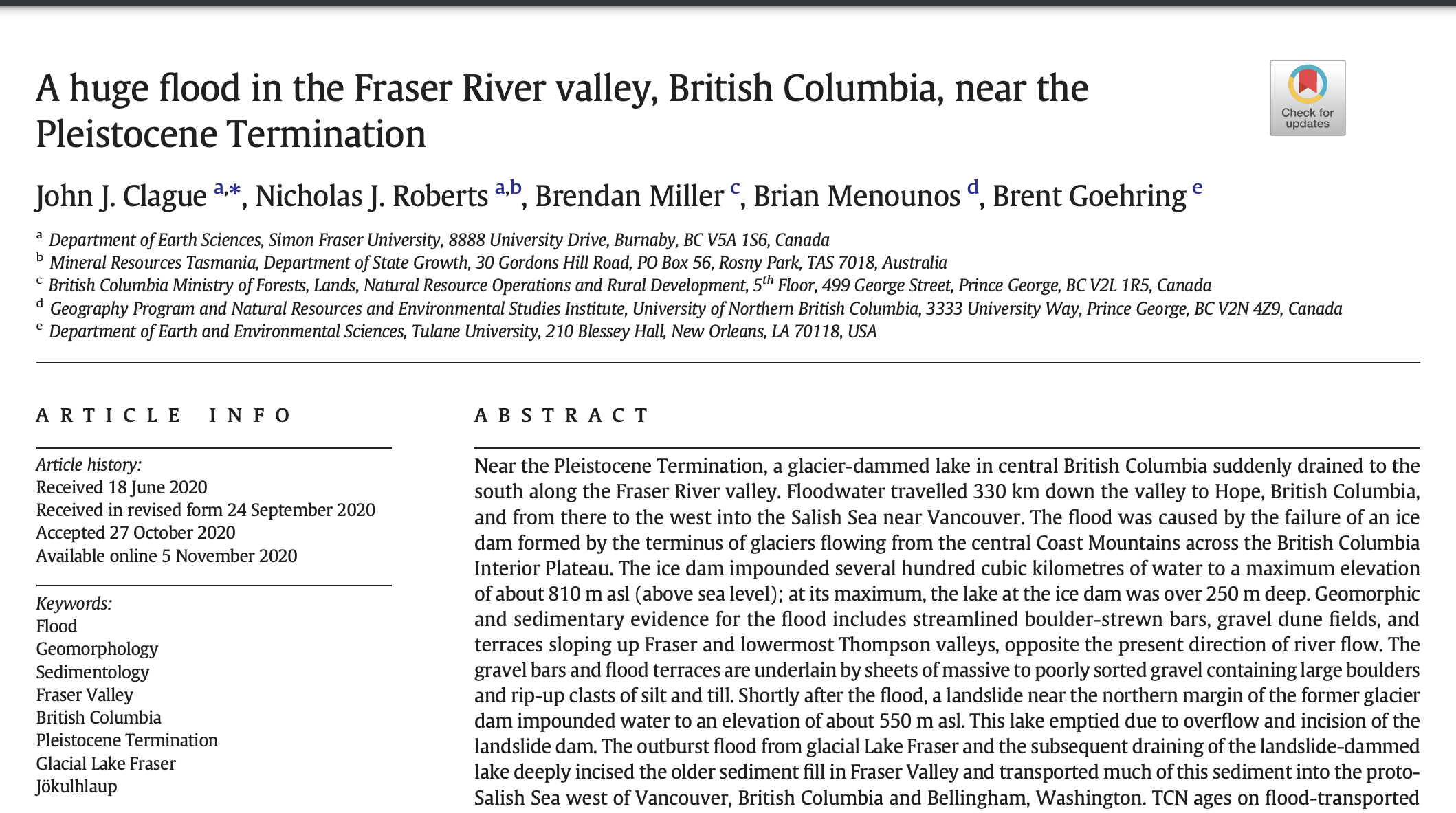

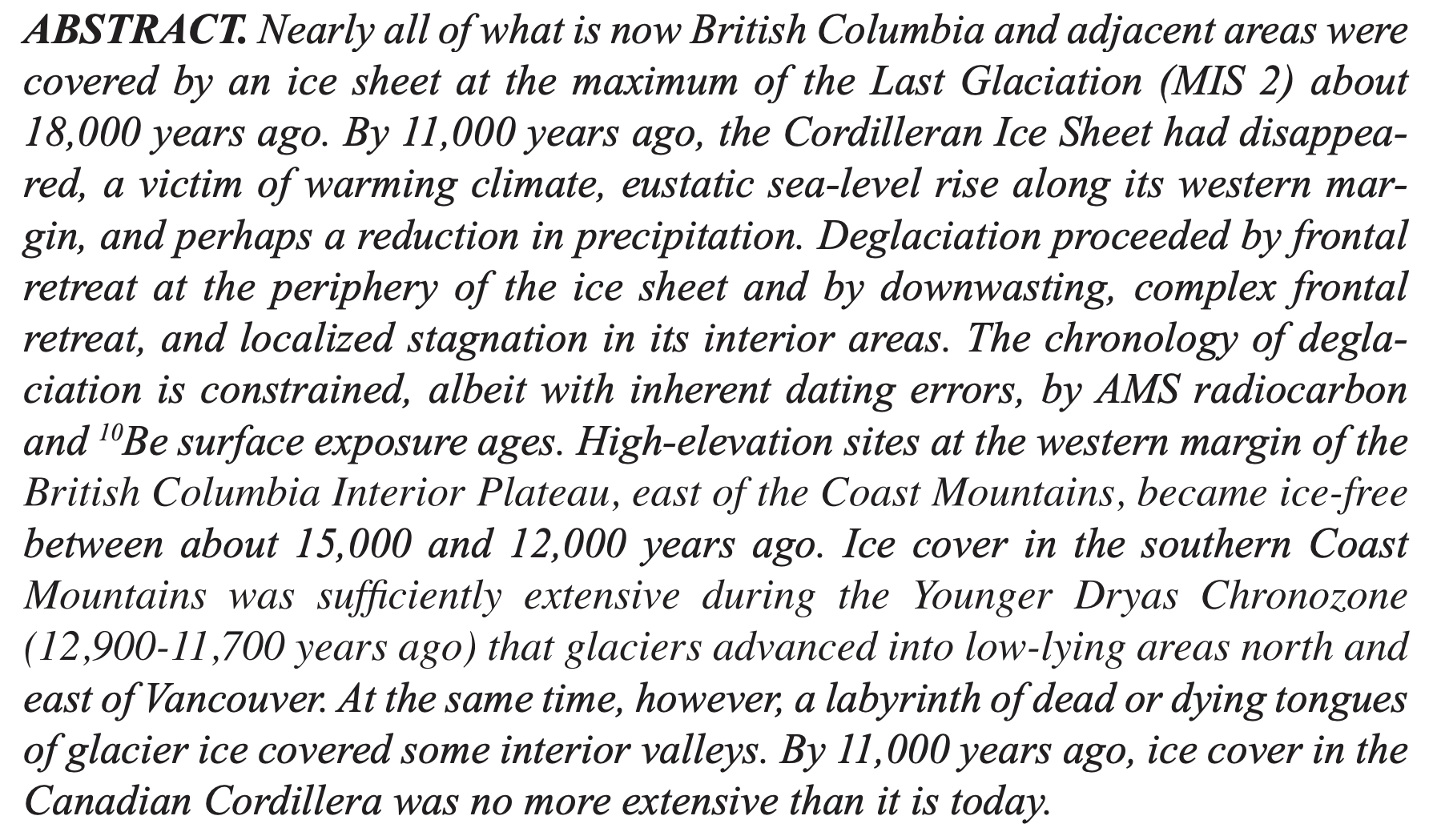

Let’s say you come across this research paper while looking for content about the Fraser River valley in British Columbia (for example, you are interested in its natural history). First, you are going to take a close look at the title. This gives you a one-sentence glance at what the paper is about. Are you interested in a flood that occurred long ago (the Pleistocene is the epoch spanning from 2.6 million years to 11,700 years before the present)? If yes, then this paper is for you and you can keep on reading it.

Now, it’s time to move on to the abstract: this is a summary (bird’s-eye-view) of what the rest of the paper is about. It lists the causes (when, what, and how) that could have triggered the flood, as well as the evidence of it such as scientifically analyzed sediment.

Next comes the Introduction:

Important to mention: here, in the picture above, you are seeing only the first couple of paragraphs of the introduction. Click here to see the entire introduction (as well as the rest of the paper).

This part of the research paper gives us an understanding of how the researchers became aware of the subject, what enabled them to form their hypothesis (An article on the scientific method coming up soon on Geo-Skills so stay tuned!), and how they decided to test it. To be a little more specific, scientists set of to discover why sediment dating to 11000 years before present, in a fiord on the southeast coast of Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada, contained Tertiary pollen derived from sedimentary rocks found only in the Fraser Lowland on the mainland of British Columbia and Washington east of the Salish Sea. The hypothesis of “large floods that swept across the Fraser Lowland at the beginning of the Holocene,” was first proposed by researchers Blais-Stevens et al. (et al. = et alia = and others) in 2003 (which you can find in the reference section of the research paper along with all other references).

This paper then sets the goal of investigating this hypothesis by studying the geomorphology and sediment found in the Fraser River valley. On top of that, the researchers compare their results with the records of other very well-documented floods from the past.

Next, we have a section titled “Geographic and geologic context,” which describes and shows beautiful & detailed maps of the places mentioned in the rest of the research paper. Our post will now skip ahead to the methods section.

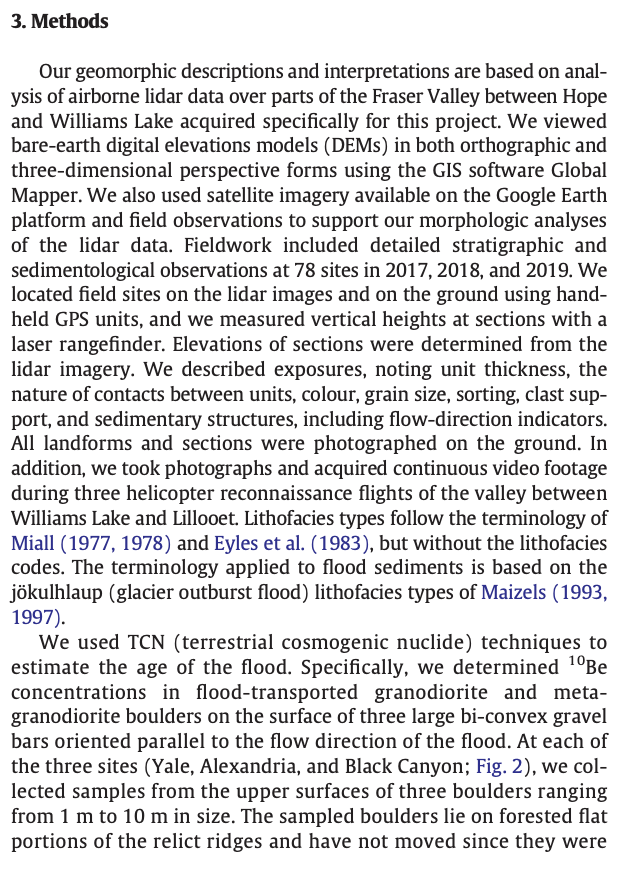

The methods section is self-explanatory: the researchers list in great detail everything they used (for example: models (such as digital elevation models), software (such as GIS software Global Mapper), other resources (Google Earth imagery), the terrestrial cosmogenic nuclide technique, etc.) to test the validity of their hypothesis.

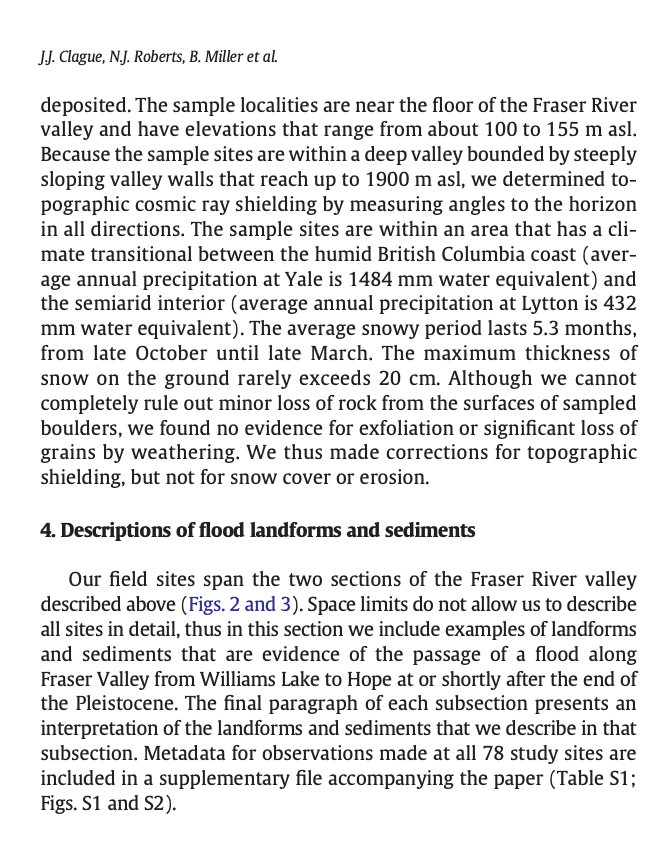

After the methods section, we read two sections about “Descriptions of flood landforms and sediments,” and “Stratigraphic evidence for a second lake phase.” The first is equipped with visuals. While we strongly encourage you to take a look at these sections, our article will now be skipping ahead to the discussions section of the research paper.

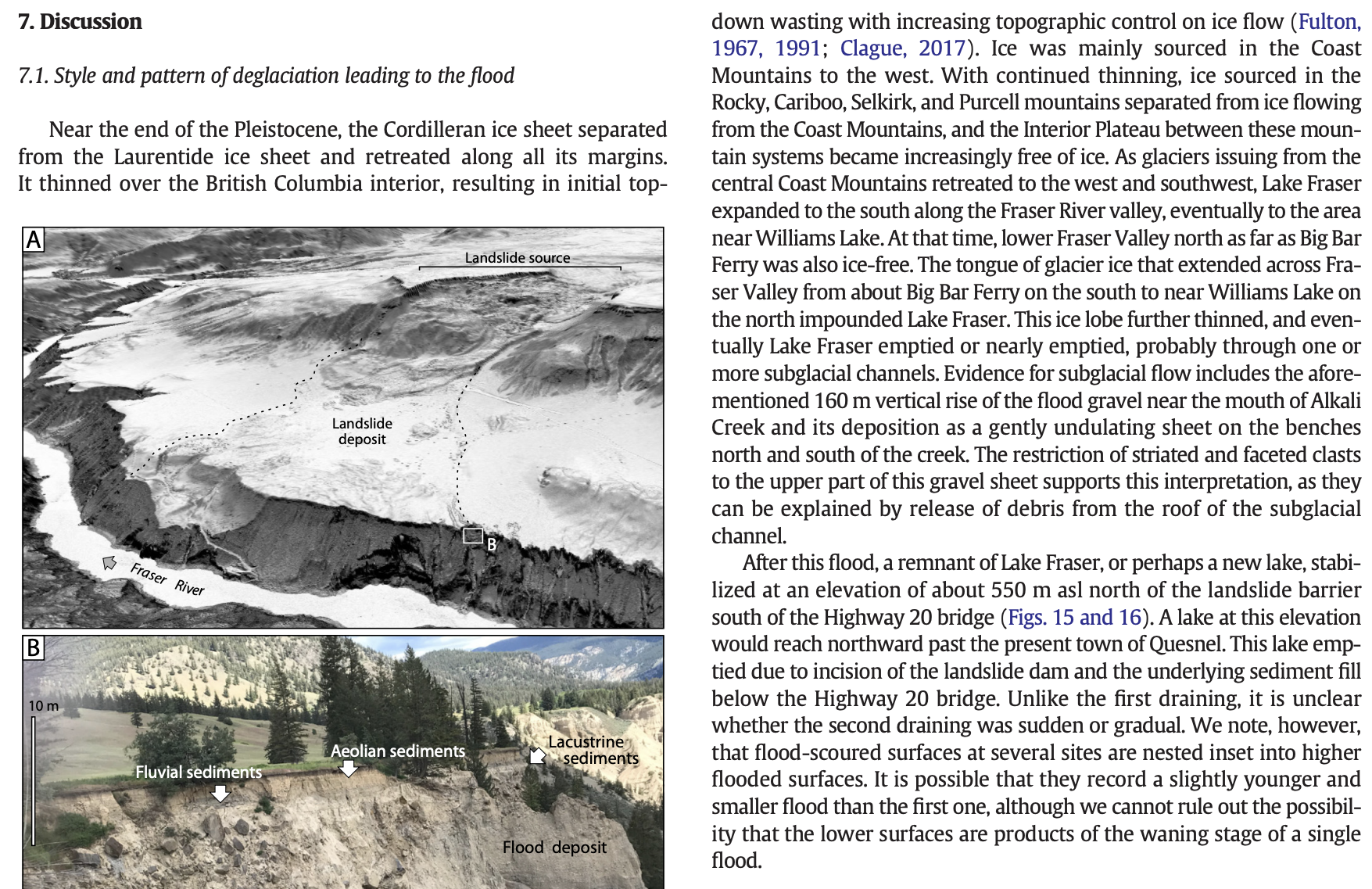

The discussion section (of which you can see the first couple of paragraphs above) is divided into the following subsections:

7.1. Style and pattern of deglaciation leading to the flood.

7.2. Morphology of Fraser Valley immediately before the flood.

7.3. Passage of the flood wave.

7.4. Formation of flood bars.

7.5. Differences between the Lake Fraser flood and other well documented large floods.

Based on the results obtained using the methods described in section 3 of this research paper, the authors make infrences on the topics listed above.

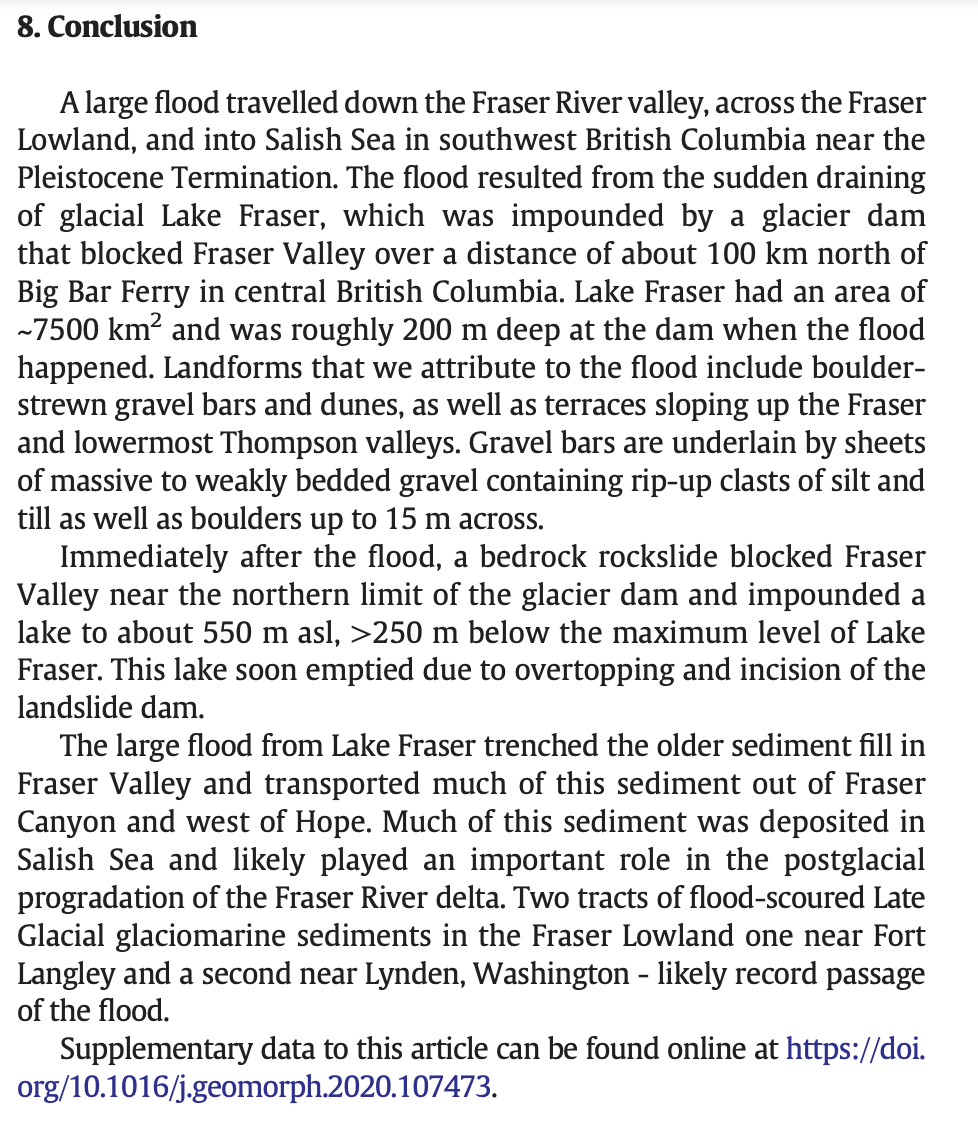

The conclusion section is very similar to the abstract. It gives us a concise description of what & how happened with regard to the flood.

Then we read that the authors have no competing interests (no conflict of interest), and the acknowledgments.

Last but not least, the reference section gives us the list of all the works cited throughout the research paper, and these can be helpful to you if you want to gain more insight on any of those.

Time for Practice!

1. Read the abstract of the paper above carefully, and write down a possible title. When you are done, click the tab on the right side of this text to see the real title of the paper. Compare your results.

“Deglaciation of the Cordillera of Western Canada at the end of the Pleistocene.”

Guess what section is represented in the picture above! Click the tab on the right to find out the correct answer!

This is the reference section (the screenshot shows the first couple of references).

Clague, J. “Deglaciation of the Cordillera of Western Canada at the End of the Pleistocene”. Cuadernos De Investigación Geográfica, vol. 43, no. 2, Sept. 2017, pp. 449-66, doi:10.18172/cig.3232.

To the left, you can see the citation of the research paper we’ve been practicing on. Assuming you would want to read the paper in its entirety, how would you find it on the internet?

“Copy” and “paste” the Digital Object Identifier (doi:10.18172/cig.3232.) into the Google Search bar. After clicking “enter,” information about the paper (as well as websites where you can view it) will apear.

Coming soon!

Coming soon!